Wendy Brown's "Undoing the Demos"

"The perpetual treadmill of a capitalist economy that cannot cease without collapsing is now the treadmill on which every being and activity is placed, and the horizons of all other meanings and purposes shrink accordingly." - Wendy Brown

Wendy Brown's essay "At the Edge: The Future of Political Theory" was on my university reading list last week. It's an interesting essay, but I became more curious about some of more incidental themes she touched on. So I read her book Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution, published 2015. In it, she argues that neoliberalism is in the process of destroying the faculty of individuals to do democracy, the ability of the state to act for social good, and even the lexicon of politics itself. I think her work is very valuable, both in describing what neoliberalism is and what it is doing. (As a fun biographical note, Brown's romantic partner is Judith Butler, the famous – and controversial – philosopher of gender and sex.)

This is a short explanation of the themes and arguments of her book, here and there with my two cents on it and its applicability to the world ten years later. All page numbers reference the first edition, published by Zone Books (Princeton University Press). I have attached a publicly available PDF of the preface and first chapter at the end of this post.

The core case of the book is that neoliberalism is "substantively disembowel[ing]" democracy (p. 9). To the extent that liberal-parliamentary democracy was once actually democratic, it is becomes less and less so. This might seem counter-intuitive at first – isn't neoliberalism just an economic philosophy based on free markets, competition, and a lack of government intervention? Brown understands neoliberalism to be more than just a policy, but an ideology that regards "all conduct [as] economic conduct" (p. 10). She defines it as "an order of normative reason that ... takes shape as a governing rationality extending a specific formulation of economic values, practices, and metrics to every dimension of human life" (p. 30). Since this definition is foundation to her entire critique, I'll take a moment to work through it.

The source of this concept of neoliberalism is Michel Foucault (who I don't know enough about to discuss). I understand "normative reason" to mean reasoning that contains certain presuppositions of value. When it becomes dominant, it becomes the "governing rationality", which is effectively the dominant ideology in the state and subsequently in society. To a certain degree, all arguments and logic in use must be consistent with the governing rationality, or else they will be unreasonable or even incomprehensible. The "specific formulation of economic values, practices, and metrics" means the concepts of the market. Efficiency, competition, "best practices", return on investment, and so forth. When these are "extended ... to every dimension of human life", all other values become subordinate to it.

An example Brown gives is the university (Chapter 6). Once, universities were valuable both for the sake of the student, in that by gaining an education they approach the Aristotelian ideal of the Good Life (p. 189), and for the sake of society at large, as an educated population will better democratically govern itself (p. 178). Now, universities frame themselves as a "smart self-investment" for students – going to university will reward the student with greater competitiveness in the job market and the "college dividend" in higher wages (La Trobe University: "Our graduates are highly sought after, with 87.8 per cent securing work within four months."). In addition, universities emphasise their output of workers with technical skills which will result in economic growth. This is also encouraged by government policy, in Australia, see the Job-Ready Graduates Program:

...if a student chooses to take out a ... loan, that money has to be paid back eventually. The last thing we as a government want is for a young person to rack up a three- to four-year university debt and graduate with a degree that has very little likelihood of helping them find work ... We also want to reduce the chances of having skills shortages now and in the future, particularly in emerging industries.

(Terry Young, Liberal member for Longman, 9 August 2021. Emphasis added.)

They key point is that neoliberalism's goal is an "economisation" of all "spheres and practices" of life (pp. 30-31). This doesn't mean a literal transformation into a market, but that the "model of the market" is applied, and human beings are imagined (and configured), solely as "market actors", homo economicus.

On the first point, the "model of the market" imagines non-economic practices in market terms. Brown analyses the second inauguration speech of Barack Obama (pp. 25-28). Here, Obama makes the case a series of progressive policies, but overwhelmingly through an economic lens, and with an economic justification. Immigration reform would "harness the talents and ingenuity of striving, hopeful immigrants". More workers would join the workforce when "wives, mothers and daughters can live their lives free from discrimination". Investing in education would put "kids on the path to a good job" and make the economy more internationally competitive (Young's justification for reform).

This marks a subtle, but radical shift in the relationship between the state, economy, and society, which Brown explores. Classical liberalism valued both economic growth and social goods – it conceived the market as serving the former and the state as serving the latter. A good society resulted when each pursued their relevant domains without interfering with the other. But neoliberalism reconfigures this idea. Now, the economy is the source of all life, and it is the state's role to serve the economy. Government not for the people, but government for the market. In Australia, the first talking point of nearly every state investment project is the number of jobs it will create, and the positive impact on the local, regional, or national economy.

For example, one might recommend a policy of increasing taxes on business profits in order to fund social services. The response, consistent with the governing rationality of neoliberalism, is that increasing business taxes will make the country unfriendly to business and "less competitive" in the market of attracting capital. As a result, foreign investment and domestic production will leave our shores, which will negatively impact the economy, impoverishing everyone. If higher taxation of businesses were good for the economy, even if it was somehow bad for the poor, rest assured it would be introduced.

On the second point, individuals are conceived of as homo economicus. Brown also uses the term "human capital". Homo economicus, traditionally, is a description of human nature – humans are naturally self-interested, perfectly rational, and calculating to optimise our pleasure. Sort of if everyone was a self-centred utilitarian. But this idea has evolved in the neoliberal age. Now, every person is their own little enterprise and entrepreneur. Once, we were all workers. Now we "compete on the job market" for the best position that we can gain. Recall the idea of education being an "investment" in oneself.

The conceptual economisation of the self has two consequences (but not only two). First, any sense of class dissolves. We are all equal on the marketplace. Not successful? Then you mustn't be working hard enough, or you haven't invested in yourself properly. You're just uncompetitive. Really, it wouldn't be fair if we gave you any advantage. In the market, there are always winners and losers – anything else would be a distortion, and market manipulation must always lead to inefficiency.

Brown does not address this, but part of this problem is addressed by "wokeness", which, in a sense, is really just another way of expressing the same idea. Non-woke neoliberalism is blind to historical and structural injustices, and blames the individual for their lack of success. Woke neoliberalism does recognise injustice, and aims to eradicate it – but the end goal is merely to achieve what the non-woke neoliberals believe is already the case. Once all injustice is solved (whatever that means), everyone is free to compete equally on the market, and finally, when some fail, it is their own fault, not racism/sexism/homophobia, etc. This is not to criticise progressive movements to end these injustices, only the neoliberalised idea of progress as removing barriers to participation in the economy – movements towards "inclusion" instead of liberation.

The second consequence is the subordination of the self to the economy. This is another radical departure from classical liberal thought. For liberals like Locke and Smith, the economy naturally resulted in good outcomes for all by means of exchange, self-interest, and competition (the classic homo economicus from before). "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest." This is no longer the case. Since individuals are "human capital", we are subject to the whims of the market. When there is an economic downturn, we should expect to – even willingly, gladly – make sacrifices. After the pandemic, when inflation was high, we heard public appeals for families to cut their spending to slow the economy down, and then enforcement by way of interest rate rises on indebted and renting households. After all, the economy is the source of all life – we would all starve to death without competition and trade. There are sacrifices in other values too – whenever they conflict with economic growth. That is why investment in fossil fuels is still necessary, even as we understand the world is hurtling towards climate collapse.

These sacrifices do not always need to be self-sacrifices. A prime example of this comes from the Trump administration's attempt to deport all undocumented immigrants in the United States. This will have the consequence of the loss of many exploited, underpaid, undocumented farm workers. The response from the (neo)liberal establishment has been that these deportations should not happen – not because it is immoral and violent to uproot people who may have been living in a certain place for years, but because they are necessary for the agricultural industry to survive. There is outcry against this new extreme level of deportation, but no outcry for the thousands upon thousands of migrants working in dangerous conditions, for low pay, and unable to complain for fear of being identified and deported. They have been sacrificed for the sake of the economy.

Brown notes that, in this way, neoliberalism can resemble fascism.

These convergences [between fascism and neoliberalism] appear in the valorisation of a national economic project and sacrifice for a greater good into which all are integrate, but from which most must not expect personal benefit (p. 219).

Fascism involves the subordination of the individual to a symbol of the collective. Where the symbol of the German fascists was the Aryan race, and the symbol of the Italian fascists was the nation, the symbol of neoliberalism is the market.

So, to move on, the state is subordinated to the economy and the individual is subordinated to the economy. But why? What end does the market serve? Classical liberals thought the market led to public goods, like an increase in total production that made goods cheaper for the poor and resulted in more taxation revenue for social programs. But under the neoliberal paradigm, the very idea of the "public" is under threat. Margaret Thatcher said famously: "There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families." When we are all individual enterprises, human capital, in what sense can we be said to have any shared interests, except our interest in the market? If we are all constantly competing and self-investing, what energy – even desire – do we have left to consider the good of the community? If we are all just capital, can we even be citizens?

Recall the economisation of political language and of the state in general. This also entails the loss of democratic and egalitarian concepts and ideals, and their conversion into economic terms. The market no longer exists to serve society. It exists to serve itself, and those individuals savvy and entrepreneurial enough to benefit from it. Again, there is no value independent from the market. Equality is equal access to entrepreneurship and the job market. Justice is an unimpeded, undistorted market. Free speech is unrestricted access to the "marketplace of ideas" (one must only look at Citizens United v. FEC in the United States to see the consequences of that idea – addressed in Chapter 5). Freedom itself is but a free market.

In practice, neoliberalism is not all-consuming. It it still restricted by more classical ideas of democracy and justice. The measure to which this is so depends on the country, and depends on the stage in time. In my economics class, I was taught the concept of market failure, where government intervention is legitimate to tackle problems of environmental destruction, or extreme inequality. This is government action for political, humanistic values. To the extent that the government still aims to improve peoples' lives for its own sake, neoliberalism is held back.

Also, while this it not addressed in Undoing the Demos (see Brown, The New Clothes of World Politics), neoliberalism has an important counterpart: neoconservatism. Neoconservatism moralises politics, turns politics into a theatre of culture war, and thus limits the scope of the state. This relationship – of beneficial antithesis – has the function of distracting us from the impacts of neoliberalism and providing scapegoats. Neoconservatism says that, if only the nation were more white/heterosexual/Christian/whatever, all of our problems would be solved. Neoliberalism provides the material basis for neoconservatism, and neoconservatism makes neoliberalism seem, to moderates, the lesser evil. Naturally, this is a false dichotomy. (As a side note, we really need better names for these ideologies).

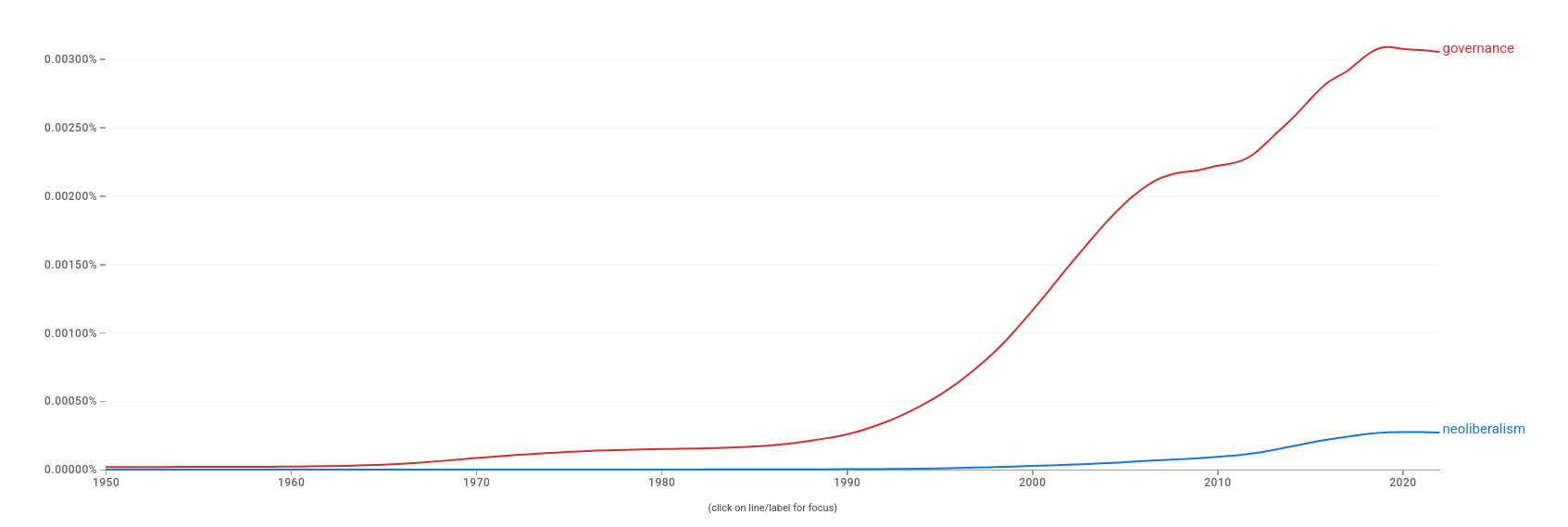

I haven't spent much time on how exactly neoliberalism has become the governing rationality of society. Brown investigates the concept of "governance" as the supposed antidote to government, and all that entails. She identifies governance as a concept believed to be post-ideological: "governing that is networked, integrated, cooperative, partnered, disseminated, and at least partly self-organised". Governance was a term borrowed from the private sector by states and NGOs. Governance, as opposed to government, replaces the public interest with "stakeholders", conceived as individuals. Public power is replaced by focus groups. The language of democracy is used, but there is no substance. Issues in societies are conceived as technical problems that need to be solved, not the object of public political deliberation. For more, see chapter 4. At the very least, the concept of governance has been heavily explored in texts, see Google Ngram below:

So, neoliberalism has been an attack on democracy and politics itself. The vector of attack is at the level of values and rationality. By envisioning the purpose of the state to be to facilitate and serve the economy, progressive reform is subordinated to this goal. The very potential for change is stifled. Thus, public political aspirations become pointless, even irrelevant. By conceiving of human beings as human capital only, any sense of intrinsic human value is lost. Individuals themselves are subordinate to the market. Their behaviour must align with the market's goals, and if the market requires it, they must make sacrifices (pp. 210-220). What potential for democracy remains, when all life is reduced to competition on a marketplace for money and power? What is the point of democracy?

Brown doesn't use the term, but I understand the political expression of total neoliberalism to be technocracy. Government becomes solving technical problems of the economy, not public power. In this scenario, what is needed isn't the people – who can be fooled, distracted, and who don't know what is best for the market – but experts who are capable of managing the economy. Any issues that don't involve the economy can be taken up by NGOs – undemocratic technical problem-solvers.

Neoliberalism seeks to destroy citizens, and make them merely capital. It is the remaking of humanity in the image of capitalism. In this world, democracy is incomprehensible.

The perpetual treadmill of a capitalist economy that cannot cease without collapsing is now the treadmill on which every being and activity is placed, and the horizons of all other meanings and purposes shrink accordingly (p. 222).

Brown's book is large, and there are some topics I haven't addressed here, including the gender of homo economicus, the intricacies of governance, and her theory of neoliberal jurisprudence. I would highly recommend reading Undoing the Demos, particularly the preface and the first chapter, which broadly cover the ideas of the book. You can find these publicly available hosted by the University of Toronto here: https://complit.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/wendy-brown-undoing-the-demos1-45.pdf.

Alternatively, Brown held a lecture on the topic in 2014 just prior to publishing her book. You can find it on YouTube here: https://youtu.be/CAgfxJ84jQs?t=870 (timestamped to skip her being introduced).

In 2019, Brown updated her views in response to Trump and other right-wing populist movements in the West. I haven't read it yet, see In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West.